Martin Heidegger's "Memorial Address," Introduction

Why this Speech is the Best Place to Begin with Heidegger's Later Thought

Why Read Heidegger?

Martin Heidegger was one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century. A German thinker, he is best known for his 1927 work Being and Time, which had a profound impact on the course of philosophy in Continental Europe. In that book, Heidegger argued that Western philosophy had lost sight of its most basic question — the question of being itself — and that this question needed to be reopened and rethought from the ground up. His work helped reshape the field of phenomenology, a branch of philosophy focused on lived experience and the structures of consciousness. It also laid the groundwork for the later development of existential philosophy, influencing major figures like Jean-Paul Sartre and Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

For my first philosophy walkthrough, I chose a text by Heidegger because I specialize in his work. Starting with a thinker I know well felt like a good way to ease into the rhythm of posting regularly.

Heidegger is also a notoriously difficult philosopher to read. And so I wanted to show you that these philosophy walkthroughs can help a general audience read difficult philosophy texts.

Why Read Heidegger’s “Memorial Address”?

I originally planned to begin these walkthroughs with Heidegger’s well-known 1954 essay “The Question Concerning Technology.” It’s one of his most important statements on the problem that preoccupied much of his post–World War II thought: the nihilism that underlies the modern conception the world. But “The Question Concerning Technology” does not really address how Heidegger envisions responding to this problem. So starting there would kind of leave us hanging.

Instead, I’ve decided to begin with his 1955 Memorial Address, which is more accessible and broader in scope. In relatively clear language, it introduces both the challenge of modern technology and the kind of response Heidegger believes is needed. It’s a better starting point for understanding his later philosophy as a whole.

As the title suggests, Memorial Address is a transcription of a speech Heidegger gave in his hometown of Messkirch, Germany, in honor of the composer Conradin Kreutzer’s 175th birthday. But Heidegger says very little about Kreutzer himself. Instead, he uses the occasion to present the core themes of his later work to a general audience. Because this speech was written for a public event, the language is less technical than in his academic writings.

Memorial Address gives us a clear first look at what Heidegger is trying to do in his later philosophy. By starting here, we won’t get lost in the details if we turn to his more difficult essays later.

Wasn’t Heidegger a Nazi?

It’s no secret that Heidegger was once a member of the Nazi party. Although he later admitted in private that joining was a mistake, he never publicly apologized or condemned the party itself. These failures—both personal and public—have long complicated his legacy. Whether his political affiliations undermine his philosophical contributions remains a matter of ongoing debate amongst scholars.

After World War II, Heidegger was barred from teaching by the French occupying authorities due to his Nazi affiliation. By the time he gave this speech in 1955, he had been reinstated. While the Memorial Address contains no explicit Nationalist Socialist ideology, the setting—a conservative region of Germany—means the theme of “homeland” he raises in the speech would have carried nationalist overtones for many listeners.

That doesn’t mean Heidegger was simply dog-whistling far-right ideas. But it does mean we can’t ignore the political and historical weight of the language he uses. These are inescapable issues we should confront directly.

This is, after all, a text about memory—about remembrance in the deeper sense. In English, remembrance suggests both recalling the past and learning from it. For some, however, Heidegger’s text may seem to silence his own previous mistakes in a way that forgets.

For us, his readers, that tension creates both a caution and an invitation. A caution: not to forget, as some may think Heidegger’s text seems to. And an invitation: to ask what these themes—homeland, rootedness, and rootlessness—might mean for us, if we remember differently. What could they become in our own experience, on the way to a new understanding of being?

Despite Heidegger’s own failings, his work still offers us the opportunity to think for ourselves.

What Does Heidegger’s Later Work Offer us Today?

Heidegger is often portrayed as an anti-technologist: a kind of romantic Luddite who longed for a return to pre-modern, rural, and traditional ways of life. And to be fair, there are moments in his writings that give that impression. But the Memorial Address offers one of the clearest statements that Heidegger was not simply rejecting modern technology. Instead, he was trying to show how we might cultivate a different way of being, one that allows for a more thoughtful and critical relationship to technology.

This speech makes it clear that Heidegger’s later thought does not call for a complete rejection or withdrawal from the technological world. It won’t ask you to delete your social media, buy a ‘dumb phone,’ or embrace digital minimalism. It’s not even a forerunner of the “slow living” movement. What Heidegger is proposing is more radical than any lifestyle trend.

His later philosophy invites us to learn how to live well in a world of smartphones, constant notifications, and AI. It’s about developing a more mindful way of engaging with technology, rather than being thoughtlessly shaped by it. Ultimately, it challenges us to become more thoughtful, less dependent people: capable of using technology without simply being used by it.

And it promises all of this by helping us learn to think in a deeper more reflective way than our culture promotes.

What Version of “Memorial Address” will we use?

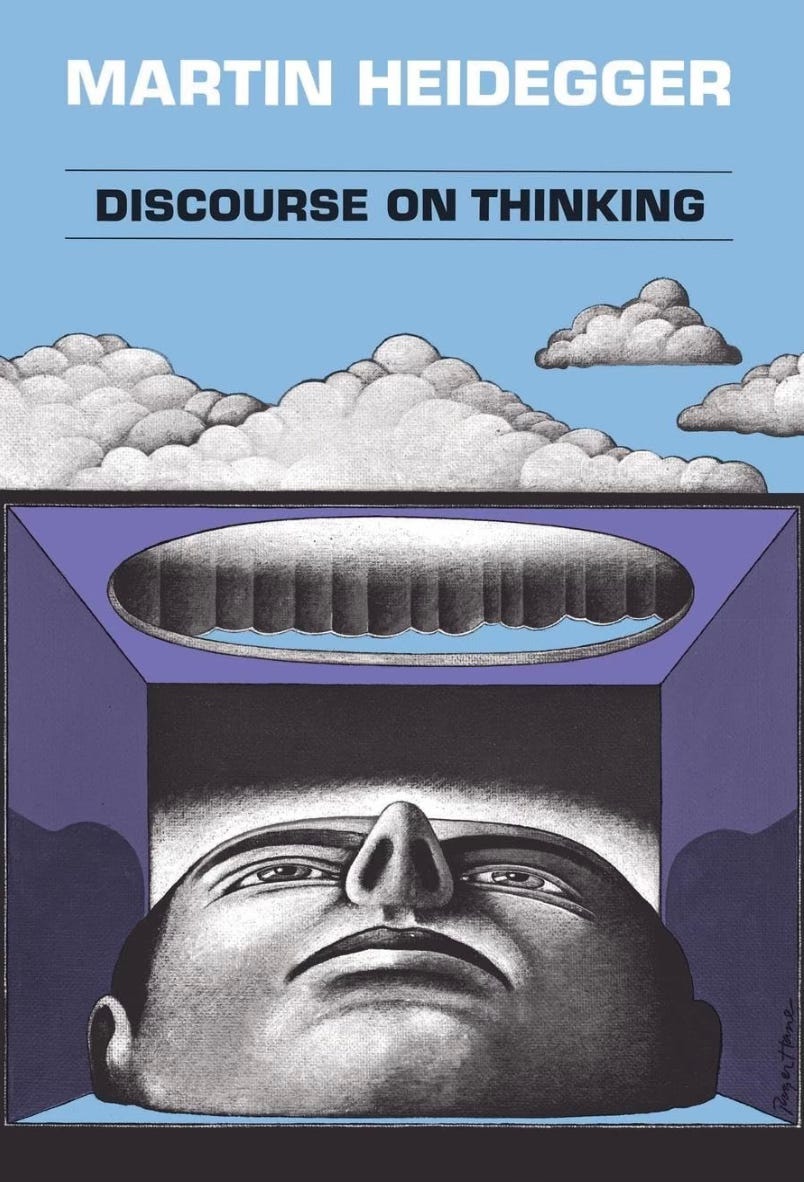

We’ll be using the English translation by Anderson and Freund, based on the German printed version titled Gelassenheit. This translation appears in the book Discourse on Thinking (Harper Torchbooks, 1966).

An electronic version of this translation is available on beyng.com. You can also likely find PDF versions of the Memorial Address through a simple Google search.

For those who would like to follow along in the original German, this text can be found in volume 16 (Reden und andere Zeugnisse eines Lebensweges) of Heidegger’s collected works, his Gesamtausgabe—again, under the title Gelassenheit.