What is Existentialism? (2) Existentialism's Continuing Relevance

What I Wish I Knew about Existential Philosophy from the Start (Part 2)

This is the second instalment in a short paid series introducing existentialism.

If you missed the beginning, you can read the first post for free here.

Existentialism is often taken to be more a style of life than a philosophy, and, having gone out of fashion like all styles do, is now best recalled in nostalgia, like film noir.1

Sometimes my students wonder why they should care about existentialism when even its most prominent philosophers rejected it.

I remember being there myself.

I came across warnings that Sartre, Heidegger, and Camus all rejected the existentialist label.

In the coming years, I’d come to learn why Heidegger, Camus, and even Sartre (at one point) denied they were existentialists.

But back when I was starting out, learning that these thinkers had rejected the label made me wonder: if they had moved past existentialism, was it still relevant for me to study today? Or had it already become obsolete and outdated?

What I tell my students now is that, like most philosophy, the early formulations of existentialist thought had their shortcomings. The key thinkers soon recognized these limits and began working toward a fuller picture, even as the existentialist label remained attached to this earlier body of work.

But that does not make the core existentialist texts irrelevant today.

In its truest sense, existentialism is not a dead tradition. It is a living idea—one that still challenges us to grapple with how to respond to the human condition.

Why did Sartre Reject the Existentialist Label?

Many don’t realize that Sartre initially rejected the label even during his most ‘existentialist’ phase.

Even before he ‘abandoned’ (I use this term loosely) his existential philosophy for Marxism, Sartre had a rocky relationship with the term existentialism. His hesitance shows us that the term itself has a complicated history and that we should be careful about what we mean when we use it.

Sartre himself didn’t invent the term existentialism: the French Christian existentialist, Gabriel Marcel, first used it in a 1945 review of Sartre’s Being and Nothingness. But the term stuck, and existentialism became all the rage amongst the general public in France.

When people would see Sartre in the cafes and streets of Paris, they’d ask him, “What is existentialism?”

Sartre would respond, “Existentialism? I do not know what that is. My philosophy is a philosophy of existence and it comes from a very complicated German philosophy, which is phenomenology.”2

Sartre was not rejecting his own work but its popular reception. He was trying to maintain some professional distance from the crowd’s watered-down version of his philosophy.

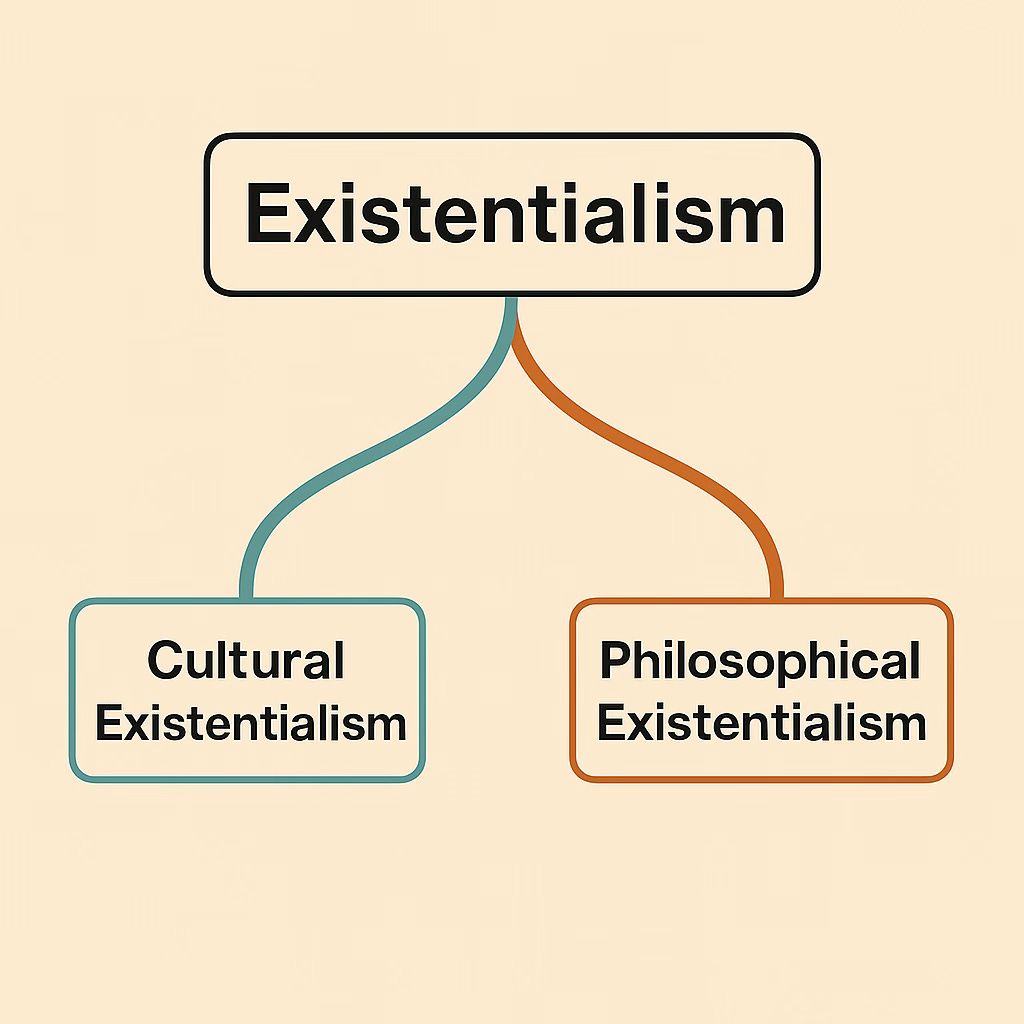

By the time of the delivery of his famous public lecture “Existentialism is a Humanism,” he had embraced the title. But this should not make us forget that by distancing himself from its public reception, Sartre was the first to anticipate the distinction between cultural existentialism (cigarettes, coffee shops, jazz, and black turtlenecks) and philosophical existentialism.

As two contemporary scholars put it:

There is, of course, a sense in which existentialism is outmoded, and we must draw a distinction here between the philosophical existentialism we defend and encourage, and the cultural existentialism that was distinctively a phenomenon of the mid-twentieth century.3

Philosophical existentialism is not a passing trend; it is a reflection on the human condition. One where we perpetually find ourselves held in a tension we did not choose. The tension between our effort to make sense of the world and the universe’s apparent indifference to that effort.

Sartre later moved beyond his earlier existential work, turning to Marxism to focus more fully on the social and historical dimensions that constrain human agency. But his earlier existentialist work still influenced his later work.

This shows us that even if our initial responses to our own human condition are partial and limited, needing revision along the way, existential philosophy invites us to keep grappling with and thoughtfully responding to the fact that we are thrown into this existential tension.

Turtlenecks may go in and out of style, but the promise of philosophical existentialism will endure alongside the human condition.

Why did Heidegger Reject the Existentialist Label?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Philosophy Walkthroughs to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.